Why don’t poisonous animals poison themselves?

Poisonous animals can be roughly divide into two categories. The first type uses poison for passive defense, such as pufferfish and poison dart frogs, which are call poisonous animals.

The second type uses poison to actively attack, such as scorpions and cobras, and is call venomous animal.

“Defensive” venomous animals use poison to poison animals that try to prey on them, so the toxins generally take effect after entering the digestive tract.

The toxins of these animals circulate in their blood and even throughout their bodies. Under normal circumstances, the cells in their bodies need to coexist peacefully with the toxins. To this end, they have evolved two main strategies:

One strategy is to mutate the target sites of these toxins.

The toxins used by highly venomous animals are generally neurotoxins . Neurotoxins act on the nervous system, and only a very small dose is need to accurately strike and paralyze the opponent’s command center, thereby quickly knocking down prey or natural enemies that are much larger than themselves.

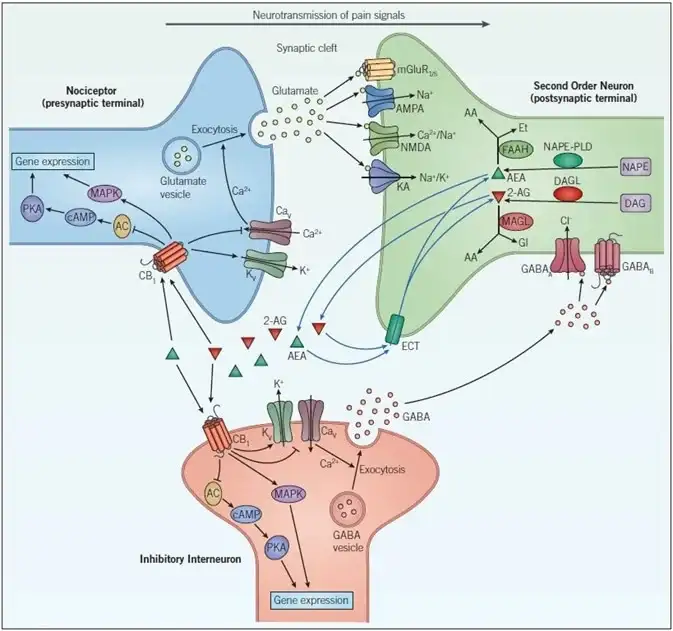

The mechanism of action of neurotoxins is generally by binding to ion channels on nerve cells .

Ion channels are the lifeblood of nerve cells. Once ion channels are inhibite, problems will arise in everything from the regulation of membrane potential to the reception of neurotransmitters, and the neural pathway will be paralyze.

However, organisms such as poison dart frogs carry mutations in sodium channel proteins . The mutated sodium channels cannot be bound by batrachotoxin (BTX), so poison dart frogs are immune to their own toxins .

Another strategy is to evolve intracellular proteins that specifically neutralize toxins . These proteins can bind toxins with high affinity, causing them to lose the ability to bind to ion channels .

“Offensive” venomous animals use their poison to kill other animals by injecting their toxins into their bodies. Their toxins work primarily after they enter the bloodstream.

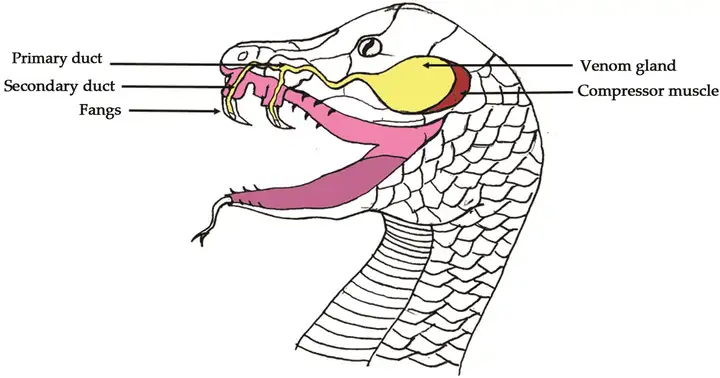

The toxins of these animals are concentrate in venom glands and are generally inaccessible to cells in the body.

For example, venomous snakes:

The venom glands are physically separate from the internal environment, so toxins do not enter the body and poisoning does not occur. This is just like urine in the human bladder does not return to the blood circulation under normal circumstances, so it does not cause any trouble.

This type of animal also uses strategies such as mutating target sites and evolving neutralizing proteins to develop a certain resistance to its own toxins; but overall, the resistance does not reach the level of the previous type of animals.

In fact, it is possible for venomous snakes to be kill by the same kind of venomous snakes. Even if you don’t die after being bite, you are likely to be poisoned.